In Tijuana, Movement's own deliver shoes, seeds of hope

Part 1: Setting the scene

The little boy with athlete's foot and a short attention span plops onto the black chair and takes off his dusty shoes.

Timidly, he lowers his feet into the bucket of warm water and flinches. His foot, he says in Spanish to the older man sitting across from him, hurts at the touch of soap and water.

The boy's name is Rafael. He's 6. And he lives in a shelter in Tijuana, Mexico, just minutes south of San Diego, Calif.

Rafael's also jittery, his curiosity in full throttle as his dark brown eyes dart to the sea of strangers in a mass of orange shirts. With frenzied precision, they fill basins with water and douse the feet of other children without homes, or without parents, or without much in the way of stability and resources.

But on this day, a Saturday in October, in the small side lot of EastLake Church Tijuana, Rafael and 500 other children who packed into vans and buses are getting something all their own: New shoes. New book bags. Clean feet. And, if all goes according to plan, a glimmer of hope that may shift the trajectory of their lives.

There's somebody in the world that loves them.”

"These kids are going to live their lives mostly feeling abandoned," says Samuel Lee, a Movement Mortgage market leader in San Diego. "They have care; they have their basic provisions maybe met but they'll never get to know what a new pair of shoes feels like. They'll never get to know what a prayer from someone they don't know feels like.

"This is our chance to do it."

He'll never say it but Lee is the architect of this exercise in evangelism. Joining with the nonprofit Samaritan's Feet International, he corralled volunteers from Movement offices across California. Together, they crossed the border into Mexico for reasons that are simple yet sublime: Outfit impoverished children with new pairs of shoes.

There's more. These same volunteers — some of them from Movement, some part of EastLake Church and some, family and friends who just wanted to help — also tell the kids things like "follow your dreams" and "never give up." In many cases, those words are followed by a prayer.

The same goes for Rafael who, before allowing Carlos Contreras to lather his feet, says no one ever told him about God or church. Contreras is a corporate chaplain. When the need arises, he provides counseling and support to Movement's San Diego employees. He's also a pastor — one who prays with Rafael and, in terms the boy would understand, tells him God is always with him.

It's unclear whether Rafael or his peers comprehend the significance of this ceremonial feet washing — a symbolic act that replicates Jesus Christ washing His disciples' feet the night before His crucifixion. But here's what Lee hopes they do understand:

"There's somebody in the world that loves them," he says. "That seed that's being planted, who knows? That person could become a doctor, maybe even the next president of Mexico. Whatever that inspiration leads to, it remains to be seen."

Part 2: Two worlds

A day before Carlos and Rafael ever meet, Lee stands on a beach he calls "the last frontier of the United States." He stands in one world, looking into another.

One universe is San Diego, the eighth largest city in the U.S., speckled with rugged mountains, a dazzling skyline and a stunning coast. The other is Tijuana, the bustling border city and tourism oasis in the Mexican state of Baja California, renown for its bars, clubs and cuisine.

In that world, on that beach, a bride wearing a teal gown basks in her nuptials. Friends and family surround her. Some 100 feet away, four uninvited guests with cameras and lenses and notebooks record and snap and write.

All that really separates these strangers, who share the same expanse of sand and rocks, are language and citizenship. And a fence. A large fence. A large fence that extends into the volatile Pacific Ocean.

The serenity of the moment ends abruptly. A border agent drives on the beach — the half that's in Mexico — and uses a megaphone to disperse the crowd. It's time for them to go home, he says. The waves are becoming too dangerous.

In the U.S., there is no such warning, no such demand. These Americans can stay so long as they heed the warning signs. The barrier is, once again, apparent.

Part 3: Crossing into Mexico

It's 7:30 a.m. Saturday, and people begin gathering at the Movement Mortgage office in Chula Vista, 10 miles south of downtown San Diego. Some branch managers and loan officers arrive after driving four hours south from Ventura County. Others come from Carlsbad, the affluent seaside town to the north.

One-by-one, they adorn orange T-shirts emblazoned with the Samaritan's Feet logo. They feast on Krispy Kreme donuts — fuel for the journey.

There's urgency in the air. In 30 minutes, they'll jump into cars and take off, falling into a convoy of vehicles that will pass through the international border crossing and transition into another country. Lee, a pastor, climbs atop the bed of his pickup truck and gives quick instructions:

- Drive aggressively. Mexico is a different country and its motorists play fast and loose with traffic.

- If you get lost (yes, some will get lost), use Google Maps. Apple Maps will send you off a cliff but Google is more reliable, he says.

Then, he refocuses. "For many of these children," he says, "it'll be the first article of clothing they've received that's new."

He leads a quick prayer before the travelers divvy into cars and drive off.

It takes less than 20 minutes to get to the border, a militarized zone with a large metal fence that divides the land, and people. Barbed wire snarls behind it for miles, a clear deterrent to anyone who considers scaling it. Customs agents with large guns stand guard and watch closely.

There are risks when you're crossing the border, even the legal way. If you seem suspicious or shaky, you're subject to be stopped. If you carry cargo that's too heavy, your car may be searched, or your merchandise confiscated.

The volunteers know this. They're not worried. Their cargo reached its destination days earlier.

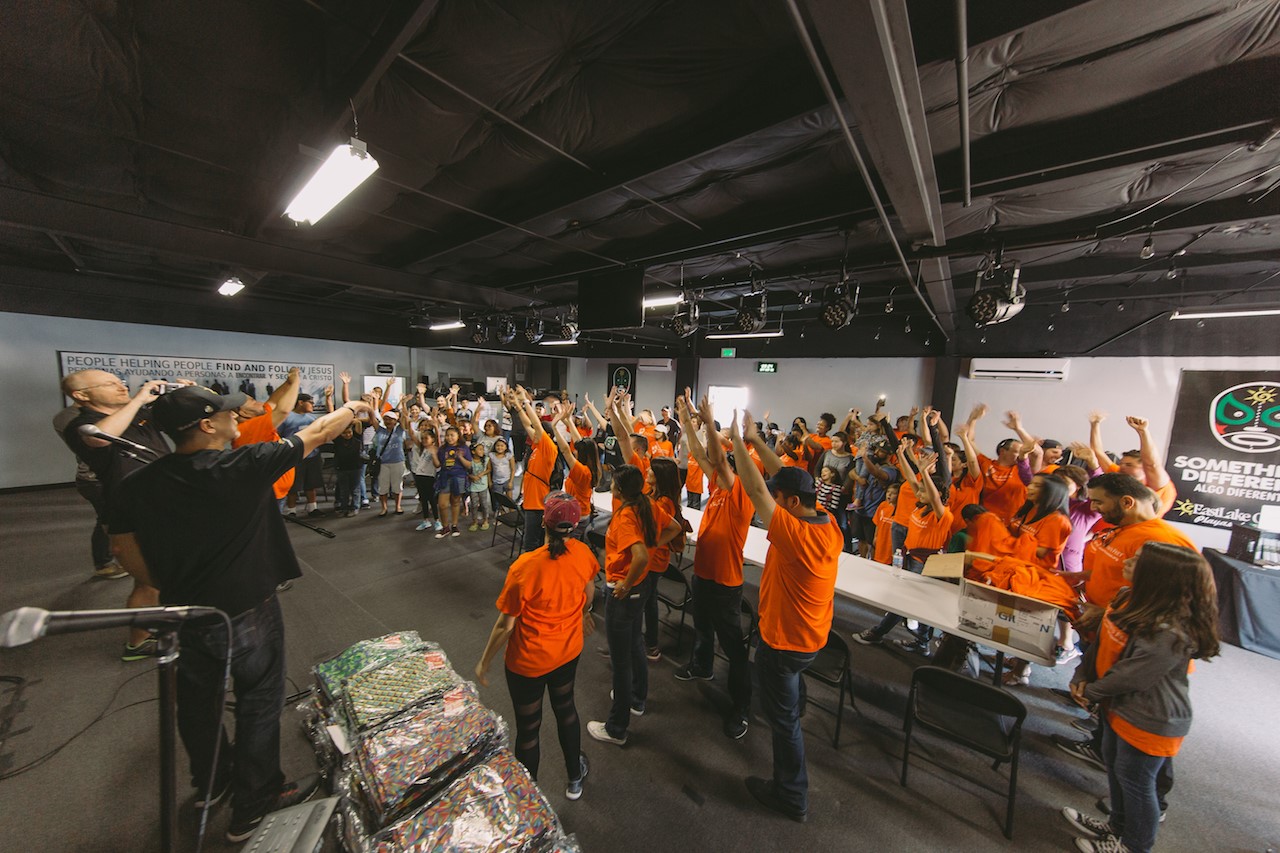

Getting into Mexico this day is easy. After a quick detour, they converge on EastLake Church, stationed in what passes as an affluent neighborhood in Tijuana. They crowd the sanctuary, pass out more T-shirts and give their attention to the front.

"We're going to change lives," Lee declares from the stage, after a wave of loud cheers and raucous applause. "We'll probably even save some. It only takes one seed to bloom and we will have an impact that will last a lifetime."

Graham Gibbs, Samaritan's Feet's executive director of U.S. projects and operations, then sets the tenor for the rest of the day: "The shoes are the vehicle we use to bring the people inside so we can have a one-on-one conversation with them and show them God's love."

"We don't just give the shoes away; we're going to wash the feet of every child," Gibbs says. "If you're going to be a leader, you need to be a servant."

Part 4: The washing

Outside, the children assemble at a metal gate and wait for the band of volunteers to take their posts. In a fashion some describe as "organized chaos," the process moves like clockwork. And quicksand.

Children check in at the registration table, where they receive a plastic wristband that includes their names and shoe sizes. Then, designated "runners" escort the children to a foot washer — "that's where the magic happens," Gibbs says — who waits for them in chairs with water, soap and towels. The runners then go for the shoes (all new and name-brand), grabbing the appropriate size and a pair of socks. They return to the washer, who packs their old shoes in a plastic bag and puts the new socks and shoes on the children's feet. Another group replenishes the water after every washing.

And that's where the magic happens. As each volunteer soaks the feet of a child, they start a conversation that touches on each child's hopes and dreams.

It's how Claudia Sandoval, branch manager of Movement's office in Oxnard, Calif., bonds with Ashley Castro as she soaked her feet.

Ashley is 9. She lives in a shelter with two other siblings. A third, whom she hasn't seen in years, lives in another state in Mexico. She also doesn't know where her parents are: She last saw her mother seven years ago. Her father? She never knew him.

She's lived in orphanages since she was 2.

She's really brilliant. She's very intelligent. She can do anything she wants."

Yet, Ashley is a gregarious fifth grader who seems unfazed by the trying ordeals life has dealt her. She's not shy at all, carrying on a conversation with Sandoval as if they were old friends. She's optimistic, too. She plans to become a doctor or teacher when she grows up.

She makes good grades, she tells Sandoval, and maintains an "A" average. In fact, she boasts, she's one of the smartest students in her class.

“She's really brilliant,” Sandoval remarks. “She's very intelligent. She can do anything she wants.”

That includes picking out her own shoes. She opts for the black and pink Nikes. She speaks a few more words to Sandoval in Spanish, gives her a hug and bids farewell.

Moments later, Sandoval is on a high.

"It's like nothing I've ever done before," she says of the feet washing. "It's so moving to be able to talk to these kids and see their vision and their world and to try to make a difference. It's more than just a pair of shoes. It's a mission of hope."

Part 5: How did we get here?

Let's pause for a moment and consider how all this happened. That means revisiting Sam Lee. Know this, though: Lee doesn't want this story to be about him. He wants it to focus on the mission and the countless number of volunteers who helped make it happen.

And it does.

But to ignore Lee's sizable contribution is to neglect an essential part of the story: The backstory.

It started last summer when Movement Mortgage partnered with Samaritan's Feet for an ambitious shoe drive dubbed "Shoes of Hope." Movement aimed to raise $300,000 for 150,000 pairs of shoes that would go to underserved children in the U.S. Seventeen market leaders, including Lee, accepted a challenge to raise at least $10,000 for the purchase of 500 shoes for kids in their communities.

Across the country, Movement employees gathered at schools to distribute shoes to over 6,300 children. They washed their feet. They prayed with them. They gave them new book bags. They planted seeds in their cities, dispersing hope and encouragement to children who may not find them in abundance.

But Lee, who pastors EastLake Church's San Diego campus, decided to take the drive outside the country's borders to Tijuana.

We'll address the critics first: Yes, Lee is very aware there are needs right in his backyard. He knows children are suffering in the U.S. He also knows of systems and agencies in the U.S. to help them. In Tijuana, "that infrastructure, those resources, do not exist," he says.

Tijuana is a city of contrasts. To some, it's the go-to place for spring breakers and vacationers looking to explore its red light district, nightlife and restaurants. To others, it's a mecca of rich culture and overwhelming beauty.

But talk to people like Lee, who are intimately familiar with the city, and they'll explain that much of that glitz is a carefully crafted masquerade — one that draws expatriate retirees by the thousands but leaves its local citizenry in dire straits.

Just beyond the rows of decadent office towers, children live in slums, where raw sewage is a ubiquitous piece of the landscape. Those same children scrounge for food. They're sold as sex slaves. On weekdays, they're placed in orphanages or shelters while their parents work the fields.

Such is the lot of 11-year-old Johnny Coeto-Monson. He loves volleyball but isn't sure playing professionally is in his future. In fact, he's not sure what's in store for his future. Sometimes, he stays with his father. Sometimes, he stays in an orphanage.

He has to, he says, while his father works a seasonal job in the fields, where for five days a week he labors and lives in a makeshift encampment. He'll return to pick up Johnny on the weekend. Sunday night, a bus will pick him up and take him back to the fields just in time for Monday morning. Instead of leaving Johnny alone, he puts him in the care of an orphanage, where at least he'll eat and have a place to lay his head.

It's something.

Johnny got new shoes that Saturday. It almost didn't happen.

Before the Movement crew ever set out for Tijuana, Lee joined forces with an organization that agreed to help transport the shoes to Mexico.

Crossing the border with valuables can be unpredictable. Border agents could seize items without warning. Motorists with heavy cargo could face heavy taxation. Transporting 500 pairs of new American name-brand shoes is a big risk.

That's why Lee trusted them. The group, he says, specializes in this kind of logistical maneuvering, specifically for charity work in Mexico. But two weeks before the distribution, the group's leader rescinded the offer of help. Lee's still not sure why.

Part 6: Operation Ant Farm

Now, put yourself in Lee's shoes (and please, forgive the pun).

You've spent months working with churches, community leaders and other organizations to ensure a substantial number of poor children get their first pair of new shoes in God-knows-when.

You've garnered support from Samaritan's Feet to turn your idea into one of its trademarked feet washing events.

You've talked this up to your friends, family and coworkers, posting on social media, filming Facebook Live videos and receiving unfettered support from your employer and colleagues.

And now the people who promised to make your delivery from the U.S. to Mexico less of a hassle tell you they want out.

"My heart sank," Lee says.

Seconds after Lee heard the news, Fito Gonzalez, pastor of EastLake Church Tijuana, gave him a call. Lee told him what happened. Gonzalez had the answer: "What do you know about God? He's all powerful. His providence is greater than all. Have faith.'"

Encouraged, Lee prayed. God listened.

In less than two hours, Gonzalez's wife, Cindy, called Lee, too. She told him she was rallying the troops — really, a small army of church members willing to haul the shoes across the border.

About the same time, Sergio and Verennice Soberanes started to think. The husband-wife team both work for Movement; Sergio is the Chula Vista branch manager and Verennice is his junior loan officer.

We were willing to make multiple, multiple trips to get all those shoes across.”

Verennice is also a former attorney who practiced in Mexico for years. And she's Tijuana born and bred. In short, she's familiar with Mexican law, has a rolodex full of contacts and knows well the hurdles one may encounter when trying to transport goods across the border. The Soberanes' also consider themselves binationals, and cross from California to Mexico all the time.

Verennice appealed to government officials and community leaders she knows. But transporting all of those goods is big business in Mexico, she says, and "you need customs' help. You need a little more money."

Sometimes, you need to pay a bribe. Verennice devised a way to get around it.

"I said let's everybody pitch in and transfer all those shoes," she says.

As for the risks, "you get caught, you get caught," Sergio says. "We were willing to make multiple, multiple trips to get all these shoes across."

They wouldn't have to go it alone.

On a Tuesday, "Operation Ant Farm" commenced. Volunteers from Movement and EastLake Church Tijuana met at a parking lot and split 505 pairs of shoes between them.

They stashed them in cars, in black trash bags, in boxes, in car boot storage spaces and decided to brave the border at rush hour. That's when thousands of commuters who work in California but live in Mexico, or vice versa, flood the crossing. It's also when customs agents are most likely to hold off on intensive inspections so they can keep traffic moving.

"Some people took 20 pairs, 30 pairs, 40 pairs," Sergio says. "I must have grabbed, I don't know, 75 pairs; (Verennice) grabbed 50 pairs and we went across."

Within a day, all 505 pairs of shoes were in Mexico. Not a single pair was confiscated.

"I just about lost myself emotionally," Lee says. "I was astounded these people had this much courage."

Part 7: New and happy

It's late Saturday afternoon at EastLake Church Tijuana, and some of the last batch of kids are resting in chairs as volunteers wipe their feet. The children have come in waves. The sun is beginning to set. People are tired; it's been a long day.

One volunteer is relentless.

She's the little girl with blonde hair and hazel eyes. She kneels down and lowers the feet of a little boy into the basin. She sprinkles water on his toes.

The girl's name is Abigail Beckett. She's 8, and daughter of a Movement Mortgage branch manager. And for the first time in her life, she's washing the feet of another child she's never met — a child who lives a world away just miles away, separated by a border, a fence.

But there is no fence today. At least, Abigail doesn't see one as she ties the new pair of tennis shoes around the boy's tiny feet. And in that innocent realism that comes from a child, she speaks the words that underscore the mood.

"It's sad because they don't have (many) shoes," she says. "But, it's happy seeing them get new ones."